>>>>>>>>>

Social-Democratic Agrarian Programme in West Bengal and Trends

in Agrarian Relations

Arindam Sen

BOTH THE admirers and critics of the Left Front Government (LFG) concur that

its spectacular success in holding on to power rests on its achievements on

the agrarian front – on its solid rural base. This year the LFG completes 25

years in office; would it not be in the fitness of things to make a fair assessment

of its agrarian programme and to examine the emerging trends in political economy

and class relations in the most stable Left-ruled state in India?

I. LF Reforms:

Three Pillars and Gaps Galore

RHETORIC APART, the immediate programme of social-democratic

reform in post-Naxalbari, post-Siddhartha1 Bengal is known to have rested on three

main pillars. In this section we discuss these one by one, and then go over to

the other gaps and failures.

A. Land redistribution

OF ALL the ceiling-surplus

land vested with the state since 1953 (when the West Bengal Estate Acquisition

Act was passed) and the year 2000, as much as 44 per cent of this land (6 lakh

acres) was obtained in the five-year period between 1967 and 1972, thanks to the

energetic initiatives of the two United Front governments; another 26% (3.5 lakh

acres) had been acquired earlier. We learn this from Table 1, which also tells

that during the LF regime the momentum declined rapidly – so much so that in the

last 20 years of its rule only 1.53 lakh acres were acquired, which amounts to

almost a quarter of what was achieved during the very short UF regime and almost

a half of what was obtained during the 14 years of Congress rule.

How about

the actual redistribution of the vested land? Table 2 shows that if one takes

1977 as the median dividing the post-1953 period of land reforms, almost 60% of

the actual redistribution (6,26,284 out of a total of 10,38,000 acres) was accomplished

before that and the rest 40% afterwards. The yearly rate of redistribution also

declined progressively. Comparing the last columns of Tables 1 and 2, we find

that 3.7 lakh acres of land vested with the state remained undistributed. A Land

Reforms Tribunal was set up in 2000 for speedy settlement of legal disputes pending

for long years in civil courts, but so far it has cleared only 13,373 acres of

land. (Paper presented by Mishra and Rawal; see below)

Litigations, of course,

are not the sole reason for lakhs of acres remaining undistributed. In a report

submitted to the WB government at its request in 1993, Nirmal Mukherjee and Debabrata

Bandopadhyaya pointed out that at the end of 1981, vested agricultural land undisturbed

by court cases amounted to 3.5 lakh acres, of which only 94,000 acres were distributed

during the next 12 years. Moreover, some 80,000 acres of land had just “vanished”,

if official records were to be believed. The surveyors showed that, together with

undistributed land, these “vanished acres” were “worth at least Rs.34 crore per

annum” and panchayats could not easily avoid “the charge of collusive misappropriation”

on these accounts.

Seven years after the publication of the Mukherjee-Bandopadhyaya

survey, Manas Ghosh reported in The Statesman (September 25 and 26. 2000) that

the CPI(M) peasant wing was “lording it over” some 3 lakh acres of undistributed

vested land and extracting 20 to 25 per cent of the production profits, which

amounted to over Rs.40 crore even in mono-cropped areas.

Whether one believes

the Statesman report or not, there is no denying that a huge quantity of ceiling-surplus

land is still kept hidden with collusive arrangements among landowners, government

departments and panchayat officials. Peasant organizations are flatly denied access

to information on this score, while the statutory “permanent committees for land

reform” under the block level panchayat bodies function as centers of corruption

and favouritism. The powerful land lobby often prevents pattadars (allottees of

pattas or title deeds) from actually taking possession of the land. Currently,

our Party comrades are conducting struggles for proper redistribution of such

land in many areas (e.g., in Britlihuda village under Chapra Police Station in

Nadia district).

Apart from the question of vested but undistributed land,

there is another, no less important issue: should not the ceiling be lowered further.

We think it should. In a state where the number and proportion of marginal farmers

are on the rise (currently 72% in official reckoning), there is no reason why

the old ceiling limits (17.29 acres for irrigated and 24.12 acres for unirrigated

land) should be kept as they are. Per acre yields have risen several times in

the intervening years, so in order to just maintain the level of egalitarianism,

the ceiling limits need to be revised downward. That would touch only a miniscule

highest rung of the rural rich and benefit an incomparably large constituency

of the underprivileged.2 But this is too much to expect from the present dispensation,

which is reportedly considering upward revision of ceilings. The upper ceiling

has already been abolished for agricultural operations undertaken by agro-based

industries and food-processing units, and considerably relaxed for urban areas;

these may well be the first steps in the ‘right’ direction!

B. Operation Barga

IT

WAS a real operation that started with a big bang. Bureaucratic red-tapism was

brushed aside, and some 8000 “camps” were organized throughout the state, between

October 1978 and June 1982, to register as many as 6,75,000 bargadars (sharecroppers).

But it took no more than about a decade for the whole thing to end with a whimper.

The NSS data pointed out that only 30.6% of all bargadars were registered and

that there was a distinct class bias, too: of the landless tenants, only 16% were

recorded, whereas in the case of big tenants the corresponding figure was as high

as 71%! This puts to rest all controversy as to which class, at the end of the

day, has benefited most from the great reform!

Several other limitations of

the programme are also to be noted. Nowhere in the state is Operation Barga (OB)

extended to bodo [boro] cultivation (summer crop of rice), although there is nothing

in the law to prevent that. Secondly, the law (West Bengal Land Reform Act 1955,

as amended subsequently) stipulates that the lessor would get half share only

when he supplies all the inputs, and will get 25% share in all other cases; but

the Operation did not attempt to enforce this in any way. In real life we find

about half-a-dozen different sharing arrangements, almost always advantageous

to the lessor.

But the most fundamental question about OB concerns its politico-economic

orientation.

Elimination of all intermediaries between the state and the actual

cultivator (who engages in direct cultivation with own or/and hired labour) –

of all rent-collectors other than the state – constitutes a key bourgeois democratic

reform. It facilitates the unhindered flow of capital into agriculture, so advanced

representatives of the bourgeoisie support this reform. Communists also fight

for it in the stage of democratic revolution because they wish to abolish the

vestiges of feudalism, unfetter the development of productive forces and clear

the arena of class struggle, making the battle between capital and labour more

direct, more intense. Way back in 1952, the Kumarsha conference of the Bengal

Provincial Kisan Sabha passed a categorical resolution saying “it is the aim of

the Kisan Sabha to put an end to the sharecropping system and grant ownership

right to the bargadar”. The 1973 CPI(M) resolution on “Certain Agrarian Issues”

also held that the “right of the tenant to the ownership of the land he is cultivating

is to be guaranteed, except to those who are lease-holders from small owners.”

The

party’s Bengal leadership, however, proved to be more prudent. Harekrishna Konar,

renowned peasant leader and a minister in the UF government, announced that sharecropping

could not be abolished by law so long as the “present social structure” existed.

Benoy Chowdhury, a minister in the LFG, wrote in 1985 that occupancy rights could

be granted to the sharecroppers only after all the tenants were properly recorded;

any attempt to do that now would lead to large-scale evictions. (Chowdhury, 1985)

The

question of ownership was thus cleverly shelved, and the CPI(M)’s middle-rich

support base kept intact. The direction of the government policy was then put

on reverse gear: a quest began for a way in which the tiller of the soil could

procure ownership not through movement but by paying a compensation, i.e., a way

in which he could just buy up the land he tills. The idea of a land bank corporation

was mooted, which would help such transactions with easy credit. Not surprisingly,

the financial institutions did not oblige the state government by supporting the

scheme, and that was the end of it all. Meanwhile, the landowners themselves devised

their own mechanism for civilized eviction – a rural equivalent of golden handshake,

as a peasant leader called it – where a small part of the land (or, in a few areas,

a paltry sum of money) is given to the sharecropper as a consolation for ‘voluntarily’

giving up all right to the land he tills. The CPI(M) was quick to take up the

cue. Just look at the following excerpts from a paper presented, at a state government-sponsored

international seminar held in Kolkata in January this year, by Suryakanta Mishra,

a front-ranking minister and a new member of the CPI(M) Central Committee, and

Vikas Rawal, an expert on agrarian economy in West Bengal:

“On the future of sharecropping in West Bengal:

“IN THE recent years, there is a trend of the

landowner and sharecropper entering into a mutual agreement under which ownership

right on, say, 25 to 30% of the sharecropped land is given to the sharecropper.

Peasant organizations have been debating whether this should be accepted…So far,

the stand of Kisan Sabha has been not to enter into or encourage such negotiations

because [in that case] all the sharecroppers will ultimately get evicted. But

with this increased urbanization, the cost of land in the vicinity of the urban

areas and even in non-municipal urban agglomerations has been increasing very

much. So if even the cost of, say, 10-20% of land is given to the sharecropper,

he will get more return from the interest of the amount than from cultivating

the land. It is clear that the non-involvement of the peasant organizations weakens

the bargaining power of the sharecroppers in this respect.

“In the past there

had been demands for making sharecroppers owners of the entire land. It does not

seem likely that the existing correlation of class forces will permit that because

a good number of landowners who leased out are not [sic! this word seems to be

an inadvertent interpolation – AS] small owners themselves. The immediately realizable

goal in respect of sharecropping is to allow a fair agreement for dividing the

ownership rights between the owner and the sharecropper…The government has been

considering about bringing a legislation on this…

“It is also debatable as to

how much share in land should the sharecropper get. The peasant organizations

have been demanding that the legislation should provide for fifty-fifty division

between the sharecropper and the landlord. While this will be possible in rural

areas, it might be untenable for the urban areas.

“… The Kisan Sabha is more

or less united to take the line that until the legislative change in this respect

is brought about, the Kisan Sabha should take the side of the sharecroppers in

entering into such negotiations and help the sharecropper get a fair share in

the ownership of land.”

So, this is the much-awaited follow-up to OB! The authors

admit that in the peasant organizations, including their own, there is much resistance

to the proposed legislation. They intervene in the debate on the side of the landlords,

asking the peasant organizations to forget the old demand and take up the role

of a dalal or intermediary in land deals (whether with a brokerage or not is anybody’s

guess). They warn the peasant organizations not even to press for “a fifty-fifty

division” in all cases. Making a mockery of Marxism, they reduce a question of

principle – of abolition of semi-feudal land relations in favour of the peasants,

of the tiller’s right to land – to logic of the market. Leave in advanced and

backward regions respectively. (Bhowmik, 1994)

As regards lessees, most of them

are poor and marginal. According to estimates of the statistical cell of the Board

of Revenue, Government of West Bengal, the average size of landholdings under

tenurial contracts is 0.97 acres. (Khasnabis, 1994) The actual condition of the

sharecropper is portrayed fairly accurately in a grassroots report, adopted at

the Bainchi-Jinna local conference (Hooghly district) of the CPI(M), December

2001:

“…Recording of bargadars did take place on an extensive scale after the

LFG came to power. But subsequently many of them took recourse to distress sale,

even of recorded land…Sharecropping is no longer remunerative. Increased cost

of cultivation and non-remunerative prices of the produce are pushing the bargadar

into a tight corner. As a result, the inclination towards giving up barga rights

is increasing…”

Well, would not many of these sharecroppers find some respite,

may be, a way out of the extreme crisis, if they are allowed to keep the entire

produce, that is to say, if they are granted ownership rights?

The overall picture

on both sides of tenancy relations thus leaves us in no doubt that there is a

strong case for granting ownership rights to the overwhelming majority of bargadars

(estimated at a total of around 25 lakhs), may be with some compensation in some

cases. For instance, a lessor who depends solely on rent for subsistence – e.g.,

aged/disabled persons, single mothers/widows and so on – may be provided with

appropriate compensation or some other special arrangement. On the other hand,

cases of reverse tenancy (more about that later on) are obviously to be exempted

(hence our slogan: ownership to the small bargadars). Some other special cases

will also be there, for the current class configuration in rural Bengal does not

warrant a simplistic implementation of the “land to the tiller” slogan. These

are but questions of detail, which can and must be sorted out through democratic

consultations among peasant organizations and concerned intellectuals, once the

basic principle of tiller’s right to land is accepted and not reiterated. But

the CPI(M)’s perpetual fear of losing the support of the so-called “middles” kept

the whole issue in limbo for some 35 years since 1967, and now with the forthcoming

legislation, the half-measure nicknamed OB is all set to be given a formal – and

not so decent – burial.

C. Panchayati Raj: Growth, Welfare and Empowerment

PROBABLY

THE most acclaimed part of the LFG reform package is the party-based panchayati

raj (PR). In terms of pioneering role, stability and regular elections, the Bengal

model no doubt ranks first in the country. Now let us briefly take stock of the

progress it has achieved so far in two key areas: (a) poverty alleviation (under

the combined impact of PR and “land reforms”) and (b) devolution of administrative

authority, and empowerment of the weaker sections of society.

A stubborn statistical

duel has been going on for quite some time now in respect to agricultural growth

rates and poverty levels in West Bengal vis-à-vis other states in India. It is

not possible here to go into details and conclude the debate but we should at

least set the record straight.

First, it is to be noted that a serious problem

was involved in the changes in methodology for collection and preparation of crop

output data. Until the 1980s the Bureau of Applied Economics and Statistics (BAES)

conducted independent sample surveys for acreage estimation and crop cuts for

yield estimation. The subjective estimates of the Directorate of Agriculture,

the state agency charged with implementing policies to boost agricultural production,

could be checked against the BAES figures, and the BAES data were generally used

as the basis of official state government estimates. In the early 1980s the DoA

unilaterally began to ‘adjust’ some BAES estimates. In the mid-1980s the integrity

of the data was further compromised as BAES sample surveys for acreage estimation

were abandoned altogether, and official yield figures were converted to a simple

average of the often quite divergent BAES and DoA estimates. Such flaws in methods

naturally casts doubts on the official estimates and inferences. (Rogaly et al,

1999)

Secondly, even if the production figures supplied by the state government

are taken to be fully reliable, much depends on choosing the base year. A growth

rate of 6.9% per annum in foodgrains can be, indeed has been, reported between

1981-82 and 1991-92. Now, in 1981-82 as well as in 1982-83, the harvests were

unusually low. If 1983-84 is chosen as the base year, the same data would show

an annual growth rate of 4.3% per annum up to 1991-92. (Sengupta and Gazdar, 1997)

Thirdly,

agricultural growth in West Bengal is not as unique as it is sometimes made out

to be: it forms part of a general turnaround in eastern India – notably in West

Bengal, Bihar and Orissa – in the 1980s. The belated spread of green revolution

to rice-growing areas seems to be the main proximate cause of this general upturn.

After 1991-92, however, there has been a plateauing of foodgrains production in

West Bengal in the 1990s: coming down from 12.7 million tonnes next year, rising

slightly to 12.9 and 13.1 million tonnes in 1993-94 and 1994-95 respectively.

(Rogaly et al, 1999) Another cause of concern, as the Mishra-Rawal paper cited

above points out, in an “increasing…shift from production of foodgrains to other

crops” and to plantations, fisheries etc., which “can threaten food security for

the poor households”. The paper admits that the LFG is yet to come up with any

action plan on this score. Having said all this, one must accept that agricultural

growth in West Bengal under the LFG has been impressive. Did that, coupled with

other measures including “land reforms”, translate into any drastic reduction

in rural poverty? The government says yes and cites in support figures from the

World Bank Report (2000), which are in turn contested by others. The controversy

took an unexpected twist in mid-March this year, when it came to be known that

the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has offered to finance and coordinate a fresh,

detailed “participatory poverty assessment” project in West Bengal because the

state, along with a few others, stands below the national average in terms of

poverty ratio. The ADB is currently the LFG’s closest partner in development projects,

and the government is favourably considering the proposal. In the mean time, let

us cast a quick glance over a few recent estimates of rural poverty in West Bengal

compared to other states and the national average.

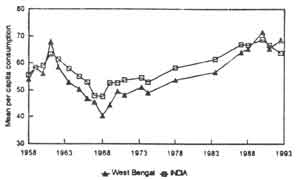

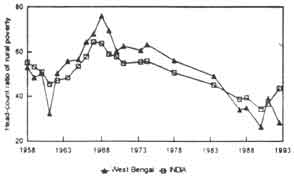

Figures

1 and 2 show that rural mean per capita consumption as well as the head count

ratio of rural poverty rose and fell in West Bengal more or less in tandem with

the rest of the country, showing hardly any sustained special achievement. We

have reproduced these figures from Haris Gazdar and Sunil Sengupta (Ben Rogaly

et al, 1999). Basing himself on the 50th Round (July 1993 to June 1994) of NSS

data, Ranjan Ray made very detailed estimates of rural and urban poverty. In

Table 3 we present some of his findings, which show that in terms of all the

available indices of rural poverty, West Bengal stood below the national average

and fared better than very few states. (Ray, 2000) On the other hand, the LFG’s

performance in providing subsidised foodgrains to the rural poor is admitted

to have been worse than that of state governments run by reactionary parties,

such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Figures

1 and 2 show that rural mean per capita consumption as well as the head count

ratio of rural poverty rose and fell in West Bengal more or less in tandem with

the rest of the country, showing hardly any sustained special achievement. We

have reproduced these figures from Haris Gazdar and Sunil Sengupta (Ben Rogaly

et al, 1999). Basing himself on the 50th Round (July 1993 to June 1994) of NSS

data, Ranjan Ray made very detailed estimates of rural and urban poverty. In

Table 3 we present some of his findings, which show that in terms of all the

available indices of rural poverty, West Bengal stood below the national average

and fared better than very few states. (Ray, 2000) On the other hand, the LFG’s

performance in providing subsidised foodgrains to the rural poor is admitted

to have been worse than that of state governments run by reactionary parties,

such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Coming

to the question of devolution of power, recent studies – including one by the

West Bengal government itself – has found that the onetime frontrunner now lags

behind some other states. Early this year, Matreesh Ghatak and Maitreya Ghatak,

after taking note of the “admire[able]…achievements of West Bengal as a pioneering

model of participatory government,” pointed out: “A recent inter-state study

by Jain (1999) covering all the major states put West Bengal not only behind

Kerala but Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka on indicators such as the power to prepare

local plans, transfer of staff, control over staff, transfer of funds…Further

more, a committee set up by the West Bengal government itself has criticised

the district level planning process involving the panchayat system and state

bureaucracy for lack of coordination and insufficient participation of the people,

or their elected representatives, at the village level…The state government

bureaucracy hands out district plans to district officials and lower tiers of

panchayats have no say in the allocation of these funds or the implementation

of these projects, unless they are requested to lend a helping hand. The amount

of money spent through this channel is much more than that is directly handled

by panchayats. Also, there is little attempt at coordinating between these two

sets of plans at the district level [Government of West Bengal, p.6],” (Ghatak

and Ghatak, 2002)

Coming

to the question of devolution of power, recent studies – including one by the

West Bengal government itself – has found that the onetime frontrunner now lags

behind some other states. Early this year, Matreesh Ghatak and Maitreya Ghatak,

after taking note of the “admire[able]…achievements of West Bengal as a pioneering

model of participatory government,” pointed out: “A recent inter-state study

by Jain (1999) covering all the major states put West Bengal not only behind

Kerala but Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka on indicators such as the power to prepare

local plans, transfer of staff, control over staff, transfer of funds…Further

more, a committee set up by the West Bengal government itself has criticised

the district level planning process involving the panchayat system and state

bureaucracy for lack of coordination and insufficient participation of the people,

or their elected representatives, at the village level…The state government

bureaucracy hands out district plans to district officials and lower tiers of

panchayats have no say in the allocation of these funds or the implementation

of these projects, unless they are requested to lend a helping hand. The amount

of money spent through this channel is much more than that is directly handled

by panchayats. Also, there is little attempt at coordinating between these two

sets of plans at the district level [Government of West Bengal, p.6],” (Ghatak

and Ghatak, 2002)

Why did the

LF in West Bengal lag so much behind the LDF in Kerala? The authors have come

up with several explanations. One is that the intense political competition the

LDF faces vis-à-vis Congress compelled it to score political points over the rivals

by launching the ambitious People’s Plan campaign just after regaining power in

the 1996 elections. More generally, “…redistributing power and resources away

from the state government, where the hold of the LDF is uncertain, to the local

government can be viewed as a rational political move. In West Bengal, given the

LF’s secure tenure at the state government level, the need for such radical reform

is much less.” (ibid)

This otherwise valid observation misses out one important

point. In the last few rounds of parliamentary and assembly elections the LF suffered

serious jolts in the rural areas too, and that might have provided the compulsion

which prompted it to introduce and emphasise mandatory village constituency (gram

sansad) meetings. In this meeting every villager is entitled, and expected, to

participate and monitor the various projects from planning to execution to review

stages. But God proposes in heaven, man disposes on earth. The fine idea of CPI(M)

state leadership is ruthlessly set to naught by the party’s local functionaries

who have developed deep-rooted vested interests in course of prolonged stay in

power and would not share power with the people. In fact, this was experienced

as early as in 1986, when an ambitious pilot project for ensuring people’s participation

in developmental planning at the village level was taken up in Medinipur by the

district authorities in collaboration with IIT, Kharaghpur. According to those

associated with the project, it fizzled out because, “firstly, the elected panchayat

representatives felt threatened that their newly acquired status would be eroded

by direct empowerment of the people and their involvement in the planning process.

Secondly, a large part of the panchayat members as well as leaders and functionaries

of political parties were employers of wage labour and they felt threatened by

the prospect of the empowerment of the working people.”

The same set of circumstances

have put paid to the subsequent gram sansad facelift too. In the bourgeois administrative

framework of decentralisation and devolution, the problem is best summed up in

the following words. “…the early success of the panchayat reforms in West Bengal

has generated some political forces that stand in the way of further, more radical,

reform…A coalition of white-collar employees (School teachers, government employees)

and middle peasants, the so-called rural middle strata, have emerged as an important

power base in the party and resist further devolution of power that a true people’s

plan would entail.”

The masses of the downtrodden, however, are wise enough

to understand that any measure of democratisation can only be achieved in course

of struggles against organs of power, not excluding the panchayats. They are engaged

in continuous skirmishes with the panchayat representatives of rich and upwardly

mobile middle peasants, who made rural Bengal in league with the police and the

state bureaucracy, over a host of issues including land and wages, relief and

development, favouritism and corruption, and so on. From avowed centres of mass

mobilisation, PR institutions have decomposed, over the years, mainly into targets

of mass movements. On our part we have been trying to lead this movement – with

such slogans as people’s supervision on panchayat bodies and devolution of power

to the gram panchayats from the upper tiers and from the state bureaucracy – even

as our representatives carry on the battle from within.

D. Potholes on the Reform Road

LET US hear, once again, from Suryakanta Mishra and Prakash Rawal: “As

the land reforms could not be combined with a large-scale provision of formal

credit and non-land inputs, the small and marginal farmers who had obtained land

under the programme were again exposed to the sections of rural society that controls

other forms of capital…Although the old types of moneylending have declined…their

place has been taken up by new types of moneylenders. It is basically a pre-capitalist

relation, though of a new type.

“…pre-capitalist relations continue to persist

in the agrarian relations and production processes in various forms. Sharecropping

is widely prevalent…informal moneylending is rampant.

“…There was a transformation

from semi-feudal landlords in the direction of capitalist landowners…most typically

they are neither feudal nor capitalist…While the land base of this class has weakened,

it is difficult to say what has happened to the overall levels of economic disparities,

say in terms of their share in…value of all assets and capital, and in value of

production. It is likely that the overall levels of disparity have not declined

very much…”

Now, have a glimpse of what the party’s lower-level cadres feel

about the burning problems: “The cost of cultivation has risen several times,

so marginal and small farmers are being forced to take loans from mahajans (moneylenders)

or, alternatively, to lease out their lands to rich farmers on seasonal basis.

Distress sale of land is also witnessed. Capitalist concentration of land is taking

place.” (From the Report adopted at the CPI(M)’s Sixth Pandua Zonal Conference,

Hooghly District, December 2001)

Well, such observations in the ruling party’s

official papers and documents reveal no more than the tip of the iceberg. We shall

discuss these issues in the light of our own experience and investigation, but

before that a few words on one major gap left untouched by the reform.

Lack

of what Mishra and Rawal call “adequate state intervention in agricultural marketing”

is a problem the ruling CPI(M) complains about all the time, but does nothing

to solve (to whatever extent possible for a state government). To insistent demands

of state procurement of at least the major crops and of crop insurance and subsidised

inputs, it continues to turn a deaf ear, proving thereby its utter incapacity

to support the farming community in this era of liberalisation and globalisation.

The reform regime has left unscathed the old agrarian marketing chains and practices,

where traders and warehouse-owners routinely discriminate against small producers.

The latter was promised help by the cooperative ‘movement’, but that was as much

a non-starter in this sector as in others. On the contrary, a proliferation of

trading intermediaries has taken place under – and in no way challenging – the

old monopolistic control over local wholesale trade. The nexus between the regulatory

state authorities and the “rurban” commercial elite, which had developed during

the Congress regime has only been strengthened. For details on the buckling of

the LFG to trading interests, readers may consult Ross Mallik (1993), and a paper

by Barbara Harriss-White in Ben Rogaly et al (1999).

II. Trends in Political-Economy and Class Relations

IN SECTION I we have considered the consequences of agrarian

reform (and the lack of it). But these do not fully describe the goings on in

rural Bengal. Closely related but basically autonomous trends in political economy

also contribute, in more fundamental ways, to the reshaping of class relations

and contours of class struggle. In this section we propose to consider some of

these broad, largely pan-Indian, trends in the typical context of Left-ruled Bengal.

A. Merchant’s Capital: Spreading Tentacles

TO BE fair to the LFG, it did

try to extend institutional credit cover to the rural poor when it first came

to power. But the success was limited and short-lived. In 1979-80, about 6% of

a total of 22 lakh bargadars and pattadars received bank loans. (Ghosh, 1981)

Even this could not be maintained because the cooperative credit structure soon

fell into a state of limbo thanks to corruption and mismanagement, while commercial

banks stopped whatever meagre advances they had extended to the poor peasants

once the latter became defaulters. The 1980s saw the moneylenders on a comeback

trail, and the situation steadily worsened ever since.

According to the latest

round of rural investigation3 conducted by CPI(ML)’s West Bengal State Committee,

mahajani loans (loans taken from village moneylenders) constituted 28.51% of the

total rural credit while credit from cooperative societies accounted for only

7.06% The rest 64.43% were provided with loans by commercial banks, but as much

as 62.19% of this loan was cornered by the above-3 bigha households which constitute

only about 28% of rural households. The below-3 bigha households, i.e., 72 per

cent, had to be content with less than 385 of bank credit. This group, however,

took more than 56% of mahajani loans. Generally speaking, the trend is for the

poorer families to depend perforce on such loans, often used up on mere subsistence

or exigencies like marriage, shradhha etc. The more interesting finding is that

a large number of middle peasants take recourse to mahajani loans because what

they get from the formal credit market do not suffice for modern cultivation.

Thus we see that families owning 7 to 10 bighas of land constitute only 5.22%

of total households in the survey area, but they take 16.57 of mahajani, 15.76%

of cooperative and 10.87% of bank loans. Usurious capital thus remains the main

source of credit not only for the poor but for the lower-middle peasants too.

The picture changes rapidly as one moves up the caste scale. In our survey area,

there are 39 households (1.43% of the total) in the 20 to 30 bigha category. Of

these, only 2 families took loans from moneylenders amounting to Rs.52,000 (1.59%

of all credit from this source), 3 took loans from cooperative bodies (Rs.1,32,000

or 16.32% of the total) and 11 families borrowed from banks (Rs.9,27,000 or 12.57%

of all bank credit).

The operation of usurious and mercantile capital takes

very many forms. The age-old system of dadan (taking a loan on the security of

the crop to be grown) is a growing phenomenon in many areas, particularly in the

case of vegetables and commercial crops, which need high investment. The harvest

is ties, and the price pre-fixed by the creditor (often a trader) is well below

the expected market price, this difference implying interest at an exorbitant

rate. The most widespread practice these days is for the trader in fertilisers,

pesticides etc. to sell these on credit and charge, say, 20% extra over the normal

price when repayment is made after harvesting, usually in cash but sometime in

crop. The imputed rate of interest in these cases ranges from 6 to 10 per cent

per month, more or less comparable to money advances repayable after harvesting.

Such exorbitant rates are sought to be justified on the ground of high risks involved:

no legal document, no collateral. In real life, however, default rate is very

low because the lenders wield direct social power over the poor borrowers; moreover,

the latter sincerely try their level best not to lose this very last resort. The

current trend of decline in interest rates in the organised credit market does

not seem to have any bearing on the informal rural credit market because the latter

operates in virtual isolation from the former – in areas where formal credit institutions

do not tread. Teachers, doctors, lawyers, panchayat employees and other salaried

people also a not very significant role in this market. Recycling of loans – borrowing

in the formal market and lending in the informal – is often resorted to by propertied

people having “proper connections”.

The small and middle peasants’ dependence

on merchant capital extends further to marketing and warehousing, and takes many

forms. To cite one, buyers and sellers meet and transact at the aratdar’s (stockist)

shop, using his weighing balance, and the latter charges around 7% (on the sale

proceeds) for this small service; in some cases he also helps the prospective

buyer and seller to come into contact with each other. The loss a small cultivator

incurs on distress sale, the ‘extra’ which the small producer of, say, potato,

has to pay for a space in the cold storage – these are only some of the more common

means by which merchant’s capital sucks out a good part of the producer’s surplus,

and in many cases even of the necessary product.

The renewed and extended domination of merchant’s capital is an unmistakable

feature of semi-feudalism – of retarded transition from feudal to capitalist

mode of production, that is – and the West Bengal experience is a striking illustration

of the “law that the independent development of merchant’s capital is inversely

proportional to the degree of development of capitalist production”. (Capital,

Vol.III, Chapter 20, also see box).

|

“The transition from the feudal mode of production is two-fold. The producer

becomes merchant and capitalist, in contrast to the natural agricultural

economy…This is the really revolutionary path. Or else, the merchant establishes

direct sway over production. However much this serves historically as

a stepping stone…it cannot by itself contribute to the overthrow of the

old mode of production, but tends rather to preserve and retain it as

its precondition…This system…worsens the conditions of the direct producers,

turns them into mere wage workers and proletarians under conditions worse

than those under the immediate control of capital, and appropriates their

surplus-labour on the basis of the old mode of production.” – Karl Marx,

Capital, Vol.III, Chapter 20

|

In other words, the crisis of capitalist transition and the domination of merchant

capital in West Bengal “tends… to preserve” the elements of semi-feudalism,

probably the most important one in the case of West Bengal is that by financing

the peasant small holding and small tenancy structure it enables the latter

to survive and reproduce itself in the face of unequal competition from developed

rich peasant farming and the pressures of market forces. Of course, it is a

losing battle but the small cultivator carries on, and the price he pays for

unviable farming is perpetual anxiety and a life standard often going below

that of the rural proletariat. The last sentence in the boxed quote – where

“old mode” should be taken to mean, in our case, not feudalism proper but semi-feudalism

in a semi-colonial setting – thus portrays an accurate picture of our poor bargadars

and small owner-cultivators.

B. Capitalist Trends in Tenancy

FLABBY AND conservative that it is, capital in India penetrates agriculture

not in steady steps sweeping away the remnants of feudalism, but in hesitant

detours accommodating and utilising those remnants. One of the many symptoms

of this is that traditional bhagehas (sharecropping) is not so much by direct

cultivation by capitalist landowners as by small-scale thika chas. The latter

refers to fixed rent (to be paid in cash or in crop) seasonal tenancy, i.e.,

a lease contract for one season or year which may or may not be renewed for

the next season(s). The advantages to the landowner are obvious: he gets an

assured, no-risk return without any monetary investment; he keeps the lessee

under constant economic pressure without any personal intervention because he

is free to change the lessee at will; there is no threat of “barga record” and

he is even free to take up direct cultivation if and when that appears to be

lucrative enough, and also to revert to lease contracts later on. Not surprisingly,

the incidence of lease cultivation is the highest in Punjab and Haryana (accounting

for 85% of all tenancy contracts while for India as a whole 47% of tenancy contracts

are for fixed money (29%) or fixed produce (18%), whereas only 40% account for

the traditional produce sharing. (Sarvekshana, October-December 1995).

For the Bengal scenario we can depend on our own investigation. According to

a survey conducted by the Kolkata chapter of Indian Institute of Marxist Studies,4

the area under tenancy (all types taken together) increased from 350.16 acres

to 401.60 acres in the survey area. Within this the proportion of sharecropping

declined from 86.70 per cent to 44.54%, that under fixed rent system (thika)

rose from 4.96% to 47.08%, and the ‘mixed’ cases remained almost constant at

a little more than 8%. The switchover to the fixed rent system is quite rapid

(in tune with the national average) but the rate is far behind that observed

in Punjab and Haryana.

Another new trend is reverse tenancy – substantive farmers leasing in land usually

on seasonal or yearly contract. It emerged as a notable trend in the 1980s and

1990s when many poor and lower middle peasants found the enhanced cost of modern

farming prohibitive, even as families with investible surplus found the high

profits lucrative and began to expand their operational holdings. There is wide

divergence of opinion as to how strong this trend is in West Bengal. In 1993,

Ross Mallick noted that the incidence was quite high. SK Bhowmik in his 1993

work took note of the presence of reverse tenancy, “though not as intensively

as in some green revolution areas.” In his 1994 article Ratan Khasnabis observed

that “such peasants [indulging in reverse tenancy – AS] are very small in percentage

terms”. In any case, the actual incidence of reverse tenancy varies greatly

not only from area to area but also from season to season and year to year because

rich peasants take to or give up this practice in accordance with the rise and

fall in profit expectations.

In sharp contrast with such profit-oriented tenancy stands the subsistence tenancy

of poor bhagchari whose net share of the produce (after deducting the expenses

he incurs on cultivation) covers just what is needed for subsistence. So what

he gets amounts, in terms of economic content, to a form – a semi-feudal form,

one might say, of wage, i.e. the value of labour power. Such tenants or agrarian

workers in disguise also come out as day-labourers in farm or off-farm employment;

in the true nature of things they personify and represent a process of painful

metamorphosis of landless/poor peasant into the rural proletariat/semi-proletariat

as a consequence of slow transition to capitalism.

We do not go into further details on tenancy relations in West Bengal; vast

literature is available on the subject (see, in particular, Comrade Sivaraman’s

two-part review article on Bhowmik’s exhaustive work (1993) in Liberation (September

and October 1996 issues). Our brief discussion, it is hoped, has brought to

focus considerable materials relating to what Lenin had described as “the formation

of capitalist relations within this very [attended by “feudal features” – AS]

renting of land”. (Lenin, 1908; emphasis in the original)

C. Modes of surplus appropriation, accumulation and domination

IMPORTANT CHANGES in conditions of cultivation (e.g., the spread of bodo paddy

cultivation, multi-cropping, the shift from mainly rain-fed to mainly irrigation-dependent

farming in many areas) and a certain degree of development of productive forces

(in inputs like HYV seeds, machinery, techniques and skills) over the past two

decades have led to appreciable changes in inter-class and intra-class relations

in our agrarian society. Take the case of new methods of irrigation.

The introduction of the green revolution package in West Bengal demanded, and

soon led to, an irrigation boom in the 1980s. In addition to traditional sources

like tanks, rivers and canals, “shallow” tubewells (those fitted with diesel,

and rarely electrical, pumpsets) became very popular and proved very effective.

Since the late 1980s, however, falling water tables led, in many cases, to the

introduction of mini Submersible Tubewells (MSTW). The MSTWs can reach more

secure water sources (more than 15 meters below ground, compared to 8 to 10

meters in the case of shallow tubewells) and this eliminates or reduces the

risks of the tubewells running dry during the peak withdrawal seasons. Moreover,

they have a command area several times bigger than the “shallows”. But the high

cost, and the reluctance of the bankers to grant loans under the “minor irrigation

development programme” except to those whom they consider creditworthy, place

these machines beyond the reach of even the upper middle peasants. In areas

where other means of irrigation are unavailable, a monopoly over water supply

is created, and the MSTW owner uses that in either of two ways: selling water

at an exorbitant rate to other cultivators in the command area, thereby extending

a hegemonic influence over them; or offering to take others’ plots in the command

area under thika lease, thereby expanding his operational holdings and profits.

Either way, he stands to gain and dominates the scene.

But the implications of this, still continuing, shift of emphasis to “submersibles”

or “mini deep(s)” as they are popularly called, do not end here. Diesel-powered

pumpsets are not only far cheaper but much more mobile and versatile: they can

be easily carried and used for irrigation from rivers, canals, tanks and also

fitted to tubewells. For middle and rich peasants with scattered holdings they

have been a great help. The MSTW, a far more fixed arrangement with a fixed

structure and command area, enhances the urge for consolidation of holdings

and concentration of land (cf the mention of “distress sale” and “capitalist

concentration of land” in Hooghly district, which boasts a large concentration

of MSTWs, in the Pandua Zonal Conference Report of the CPI(M).

At another level, the rapid depletion of ground water caused by them is believed

to lead to arsenic poisoning (over 2 lakh people in 7 districts in the state

reportedly affected by the ailments), and also threatens the availability of

groundwater in the future. The problem peaked in the mid-1990s when the experts

blamed the excessive withdrawal of groundwater also for shortage in the state’s

main canal-feeding reservoirs (The Statesman, 11 December, 1995). There was

even talk of purchasing water from Bihar. The 1997 bodo paddy faced deep crisis

in districts like Murshidabad, Birbhum, Howrah and Hooghly. All this forced

the state government to monitor and restrict the installation of new MSTWs,

thereby preserving and strengthening the water monopoly of existing owners.

The latter freely exploit their grip over this absolutely unsubstitutable input

to behave like “waterlords” and charge an absolute rent, so to say, on dependent

cultivators. Community MSTWs do supply water at a much cheaper rate, but they

are grossly inadequate to meet the rising demand, and the LFG seems to be in

no mood to ensure collective water rights to the less substantive sections of

the peasantry.

Like sale of water, hiring out tractors and other implements like diesel pumpsets

have emerges as major means of extending hegemony and appropriating surplus.

In many cases, ploughing by tractor becomes even technically necessary and a

smallholder has to depend on the goodwill of a big cultivator of an adjacent

holding to get his tiny plot ploughed by tractor simultaneously with the bigger

holding. He makes a good payment for this service, of course; still he feels

obliged because refusal by the owner/hirer of the tractor would put him in a

fix. New ties of dependence thus grow up – new forms of what used to be called

patron-client relationship. The monetary gain is also great: many a capitalist

farmer is known to have bought his second tractor with the profit made simply

by hiring out his first. In fact, reinvestment of surplus in modern implements

(and in trade) is generally believed to be free from the hassles associated

with very big landholdings and to yield safer, higher returns at least in the

short run. This is the main factor (not the ceiling law), which explains why

the degree of concentration of modern agricultural machinery is much higher

than that of land – a fact brilliantly brought out in the Party state committee’s

rural investigation report.

In this survey we found that households owning more than 15 bighas (approximately

5 acres) of land constitute 4.57% of rural households but own 34.91% of all

arable land, 71.53% of tractors and 84.5% of “pump-shallows”.5 If we calculate

the coefficient of concentration (percentage of any particular item – say, land

– owned by a particular size-class divided by percentage of households in that

size-class) for each item, we find that it is 7.66 for land (34.91 divided by

4.57), 15.65 for tractors and still higher at 18.50 for pump-shallows. But this

does not mean that the top rungs of rural society are loosening their grip on

land; the very opposite is true. On the basis of NSS data, Dipankar Basu calculated

that the value of the coefficient of land concentration in the 5-acre-plus category

has increased from 4.81 in 1972 to 5.94 in 1982 to 7.19 in 992. (Basu, 2001)

These findings tally perfectly with ours. It appears that the rising trend has

continued, reaching 7.66 in 2001.

We can therefore infer that during the LF rule the upper middle and rich peasants

have, thanks to their incomparably better access to capital-intensive technology,

actually consolidated their relatively small (compared to the past and to certain

other states) advantage in landholding. They also have fanned out into sundry

agro-related businesses like mini rice mills, fertiliser and pesticide retailing,

petty moneylending, and so on; but land still remains the base of their socio-economic

prosperity and influence.

It is the top rung of these substantive farmers that constitute the Bengal version

of kulak class, the principal target of class struggle today. They often appoint

managers to supervise their sprawling operations, send their sons (rarely, daughters

too) for higher education in metropolitan centres and maintain close relations

with dominant political parties. They wield the maximum social authority and

control political power at local levels, providing the funds and materials (rice,

liquor etc.) needed for mobilising votes. They have no qualms about changing

sides and such shifts in their support played not a small part in the Trinamool

Congress (TMC)-BJP challenge even to the rural bastion of LF. It is they who

take the lead in uniting the rich and middle peasants against he rural poor

(on wage questions, on developmental issues like priority in electrification,

the location of, say, a community tubewell, and so on) as well as in tackling

the movemental forces with the power of money and political connections. Unlike

their counterparts in Bihar, they do not keep private armies, but, if need be,

can get the same purpose served by the police and CPI(M) cadres or TMC/BJP/Congress

muscleman. For a graphic illustration of the ways of this class vis-à-vis the

rural proletariat, read the story of Dadpur, reported in Sub-Section E, below.

D. Subsistence farming and economic diversification

AGRARIAN ECONOMY in West Bengal continues to be a small peasant economy, but

one that draws support and substance from a spurt in multiple economic activities

in the non-farming sectors. In fact, rural Bengal at the turn of the century

is marked by a queer coexistence of two opposite trends: (i) continued and renewed

centrality of subsistence and supplementary farming and (ii) growing monetisation

and diversification of the non-agricultural economy. “About 72% of the producers

in rural West Bengal”, Mishra and Rawal pointed out in their paper, “…produce

primarily for their subsistence and not for the market.” In addtion to this

subsistence farming by small cultivators, one also witnesses among wage workers,

the spread of what we have called supplementary farming. A large section of

wage earners in agricultural and/or other jobs try and arrange for producing

at least part of the rice required for consumption on own or leased-in land.

According to the Rural Labour Enquiry, 1993-94, almost half of rural labour

households in West Bengal possessed small amounts of land – as against less

than 6% in Punjab, less than 15% in Haryana and less than 25% in Kerala and

Tamil Nadu. (Let us note in passing that this indicates a particularly sluggish

differentiation of the peasantry – which is a function of capitalist development

– in West Bengal.) Such otherwise irrational and unviable farming can actually

take place because the producer deprives himself, and perhaps, his family members

too, of the wages due to them. This is his survival strategy, particularly for

the slack seasons when jobs are difficult to come by, and grain prices are particularly

high.

Side by side with subsistence and supplementary farming, we notice a growing

diversification of the rural economy manifested in the proliferation of off-farm

employment and sideline occupations. According to preliminary reports of the

latest (2001) Census, there is a large exodus of workforce from cultivation

to “household industries,” small rural industries, salaried jobs, professions

etc. so much so that for the first time in history, the proportion of main workers

engaged in cultivation (cultivators and labourers taken together) has come down

to 43%!

Well, that does not contradict what we see in real life. A big – in many cases

the bigger – ever-changing proportion of those known as khet majoors (agrarian

laborers) actually get an equal or higher number of work days as dinmajurs (day

labourers in unspecified jobs – such as in brick kilns, rice mills, various

development projects like Indira Awas Yojana, minor irrigation projects and

so on. With extensive urbanisation and the development of roads, markets, warehouses

etc., occupations like rickshaw and cart pulling, carrying headloads, working

as cleaners and garage assistants, hawking, operating small shops and so on

now offer temporary or fulltime employment to a large number of people, specially

the new entrants into the labour market. As for sideline or auxiliary occupations,

mention must be made of poultry, livestock breeding, fishing, cane work, processed

food preparation, beedi making etc. participation of women has increased several

fold in these areas, and to some extent in agriculture as well. Moreover, poor

people have devised ingenious ways of augmenting family income. Many of them

lease out ponds (the owner is to be paid a certain amount of money, take up

Poshani [rearing cattle], say, a cow owned by another person – on condition

that the first calf will go to the caretaker, who can keep it or sell it while

the owner gets the milk or vice versa; actually there can be innumerable variations

like these) and engage in such activities on an increasing scale.

What is the economic significance of this? An attempt is being made in some

circles to project these, particularly the Census findings, as yet another great

achievement – a sign of (capitalist) development spilling over from agriculture

into other areas. Do the textbooks not tell us that economic progress entails

an expansion of the industrial and tertiary sectors vis-à-vis agriculture? Well,

in view of the various indices discussed in this essay, such an inference would

sound utterly ridiculous. Judged in that overall context, the trends mentioned

in this sub-section only point to a rural economy where agriculture, stagnating

in terms of forces and relations of production, can no longer function as the

mainstay of capitalist growth, which therefore takes place by other distorted

means.

E. Trends in labour relations

|

The Downtrodden are Standing Up

IN MANY ways it was Karanda re-enacted. Thatched houses of agrarian

workers in the Kehabpur-Sompara-Ghoshpur cluster of hamlets under Dadpur

Police Station of Hooghly district were gutted on 14 February, two days

after seven worker leaders had been arrested amidst severe police repression

on the poor households. There was no loss of human life because male members

had already been absconding and others managed to make good their escape.

Everything else, including paddy and cattle were destroyed. The story

began in November last year when the khet majoor demanded a wage increase

of five rupees for ordinary labourers and Rs.20 for those involved in

the particularly arduous work of carrying the produce from the fields

to the granaries. The wealthy employers flatly rejected the just demand.

The workers struck work. The paddy was ripe and began to rot. After a

few days the employers had to bite dust and accept the demands. Seething

with rage they decided to punish the workers, first by abandoning the

impending potato cultivation and by using migrant workers for the next

crop, i.e., bodo cultivation. The first part of the economic vendetta

was successful, with the workers pushed into a state of semi-starvation.

Then, in February, the employers actually started hiring in workers from

outside. The agitating labourers physically resisted and foiled the scheme.

The police was called in. Repression started on the 12th February, culminating

in the midnight fire two days later. Like Karanda (in Burdhman district),

this area is located in one of the most advanced belts of “green revolution”

in the state, and is a CPI(M) stronghold. Class polarisation is unusually

sharp, but both sides owed allegiance to the ruling party. The arrested

were CPI(M) members/activists, including the ex-panchayat representative

and labour leader Sukumar Murmu; the burnt houses also belonged to party

followers. Leading the employers was Mohammed Sirajuddin, a typical kulak

leader of the CPI(M); influential member of its Polba-Dadpur Zonal Committee,

a teacher and owner of 30 bighas of high quality, triple-cropped land

with a MSTW. The big difference with Karanda was that there the khet majoor

comrades had already crossed over from the CPI(M) to our Party. Their

political activism had become a much greater threat. So the scale of repression

was much higher. But in terms of independent (in the truest sense of this

overused word) class assertion of the agrarian proletariat, the unsung

heroes of Keshabpur-Sompara-Ghoshpur have held out a new promise, a great

hope.

|

WEST BENGAL shares with most other states a number of recent trends in agrarian

labour relations: (a) growing off-farm employment, (b) a shift from a permanent/attached

labour to casual labour and from (c) intra-village labour employment to conjoint

employment of local and migrant labour, (d) progress from beck-and-call service

and extra-economic coercion to voluntary contractual arrangement including group

contract and (e) a marked increase in independent class action on the part of

agrarian labourers coupled with more collective (rather than personal as in

the past) operation by the capitalist farmers. Let us now see how these general

trends take on particular forms in West Bengal.

We have already taken note of (a) while discussing the growing diversification

of the rural economy. As regards (b), the main aspect is the dissolution of

old landlordism and, with it, the end of traditional labour service and debt

bondage sometime extending across generations. But that does not mean a complete

end to all sorts of informal, often disguised attachment relations along caste,

familial and economic lines. The traditional mahindar (attached labourer on

24-hour duty on a nearly permanent basis) is a rare figure today, but often

the old system is recreated on a yearly contract. The chosen labourers also

double up as field supervisors. Even in the case of free workers big farmers

often strike up some sort of special understanding with some of them involving

some small favours in return for assured supply of labour during peak seasons.

The rich peasants prefer to lease out their separate plots to more than one

poor/lower middle/landless peasants for bodo cultivation, with an implicit understanding

that the lessee(s) with his family members will provide wage labour to the lessor

during aman or aus crop on priority basis. Modern cultivation, with its stress

on time management, is thus prompting landowners to recreate pre-modern dependencies,

often mutual, in numerous ways. Such attachment, though voluntary and less than

permanent (usually covering one or a few years), hampers the development of

class solidarity among the wage-workers. The tiny section involved in such special

arrangement usually hesitate to join strike struggles because they do not wish

to spoil the source of assured employment in the expectation of a small and

uncertain increase in wages.

Now let us consider the third point (c). If the vestiges or new forms of “patron-client

relations” add to the difficulty of organising the agrarian workers in their

militant class organisations, so do large-scale migrations. Workers come from

most parts of the state as well as from the eastern and southern districts of

Bihar, seeking employment in the main double crop paddy and potato growing district

of Bardhman, Hooghly and a few other districts. The foremost source districts

are Bankura, Birbhum, Malda, Murshidabad, Jalpaiguri, and the North and South

Dinajpurs.

The potential as well as the actual use of migrant workers help employers in

destination areas to keep the wage level suppressed. In the source areas, on

the other hand, we find it difficult to build stable organisations of agrarian

workers because its members are frequently in the roaming mode. Those who stay

back in these areas sometime find themselves in a potentially advantageous position;

they can utilise the limited supply of labour to press for higher wages. But,

more often than not, this is offset by other difficulties: demand (of labour)

itself remains low and most advanced and youthful elements are not available

in the village at the opportune moment since during every peak season they go

out in search of work. The outmigrants on their part face all kinds of hardships,

arbitrary dealings and awkward situations – e.g., when wily employers try and

use them as blacklegs against striking local workers – but unorganised and away

from their own soil, seldom can they put up an effective resistance.

As for point (d), all wage labour is by definition contractual, but at least

a couple of new features merit our special attention. One, the labour haat.

Workers and employers from nearby (and also rather distant, but not very far)

villages meet in an open field in the morning and the latter choose and pick

the required number of labourers for the day. Only some – usually a minority

– of the workers can sell themselves. Quite often a worker who leaves home at

daybreak comes back at midday empty-handed (he has spent his pocket money on

to-and-fro bus fare unless he is wealthy enough to own a bicycle) and with empty

stomach, only to find his wife and children waiting in anxious expectation.

The labour haat is a crude, primitive form of capitalist labour market, brought

into being by shortage of employment opportunities and developed communications.

It differs from migration in that the latter takes the worker to a distant place

for fortnights/months on end, whereas the labour haat entails daily commutation.

In this market labour power is bought and sold, just like vegetables in the

morning haat, through hard, direct bargaining at a price approximating the ruling

market rate. Almost always (except during short peak seasons) it is a buyers’

market and the sellers, because they are not organised, gain but little from

their enhanced mobility.

Secondly, phooran, or the system of hiring a group of local workers for a specific

job (say, harvesting the crop on a particular field) against an agreed lumpsum

payment, is growing more and more popular, particularly for harvesting work.

The workers strain themselves to the maximum, just as piece-rate workers in

industries do, so that they can finish the job quickly and take up another shift

(or two) the same day. For a few days their daily earning soars, while the employer

gains by reaching the harvest to the market ahead of other farmers. But the

process sidelines the famale and the middle-aged workforce, and quickly drains

out the vital energies of the younger ones.

As for the last-named trend (e), the situation in west Bengal is definitely

different from all other states. Here the CPI(M) deviated from its national

policy by refusing to form a separate agricultural workers’ union, preferring

to keep the “dangerous” class tied to the middle-rich peasant leadership of

the kisan sabha. A belated realisation of growing alienation from the agrarian

workers recently forced the party to launch a separate organisation for them,

but the essential class character of the CPI(M) has ensured that it remains

a perfect paper organisation. On the other hand, communist revolutionary organisations,

including our Party, have had successes in labour organising in few areas. Under

the circumstances, independent class action of the rural proletariat and semi-proletariat

is possible only by breaking the powerful political hegemony of the CPI(M) and

fighting against the relief-reform-terror regime of the LFG. But that is the

path they are taking – here and there, often unnoticed, slowly but surely. The

latest example of this emerging trend was witnessed in Hooghly district, not

very far from Kolkata (see box).

III. Towards a Thorough Reinvestigation

THE FACT that West Bengal has seen not a single sustained movement of the rural

poor over the last two decades despite our best efforts cannot be explained

simply by referring to the CPI(M)-LFG’s class collaborationist policies and

terror tactics. For these policies to succeed, for the whole social-democratic

politics to succeed, a proper material foundation and a suitable correlation

of class forces were needed. And these were available, first, in the development,

however lopsided, in productivity and productive forces during the 1980s; and

second, in the suitable changes in the production relations which gave rise

to new dependencies or symbiotic relations among mutually opposed classes and

strata. But today we see agrarian growth tapering off, the elements of conflict

inherent in various dependencies and attachments coming to the surface under

the impact of the national agrarian crisis, and new fault lines coming up in

the social base on which the present regime survives. Fresh scope is therefore

certainly coming our way to end the stalemate. But that demands, inter alia,

a deeper, more comprehensive study of the agrarian scene and a better systematisation

of our rich but scattered ideas on the dynamics of class struggle in a state

which saw the extreme revolutionary offensive followed by the extreme counter-revolutionary

terror and then fell into a sordid social democratic equilibrium.

References:

Basu, Dipankar (2001): Political Economy of ‘Middleness’ Behind violence in

Rural West Bengal, EPW, April 21

Bose, Biman (2000): Expose TC-BJP campaign of slander and violence––unleash

Mass struggles, Peoples Democracy, September 24

Bhaumik, Shankar Kumar (1994): Tenancy Relations and Agrarian Development––A

study of West Bengal

Ghatak, Maitreesh and Ghatak, Maitreya (2002): Recent Reforms in the Panchayati

System in West Bengal toward Greater Participatory Governance? EPW January 5

Ghosh, Ratan (1981): Agrarian Programme of the Left Front. Government, EPW,

June (Review of Agriculture)

Government of West Bengal (1995): The Recommendations of The State Finance Commission,

1990-95

Khasnabis, Ratan (1994): Tenurial Conditions in West Bengal : Continuity and

Change, EPW, December 31

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich: The Agrarian Question in Russia Towards the Close of

the Nineteenth Century, Collected Works, Moscow 1973

Marx, Karl: Capital, Vol. III, chapter 20

Ray Ranjan (2000): Poverty, Household Size and Child Welfare in India, EPW,

September 23

Notes:

1 Siddhartha Shankar Ray, as the Chief Minister of West Bengal during the early

and mid-1970s, was responsible for the worst repression let loose on communist

revolutionaries and left and democratic forces.

2 Using official figures, Dipankar Basu calculated that “by bringing down the

ceiling on landholdings in 1997 to 10 acres, the LFG could have potentially

made available an amount of land that works out to 98% of all the land that

it has managed to redistribute for the past 23 years...And this would have adversely

affected only 1.36% of the rural households! (Basu, 2001)

3 The survey area covered 4464 families spread over 7 districts – Nadia, Bardhaman,

North 24 Parganas, Hooghly, Murshidabad, Darjeeling and Jalpaiguri – with the

first two accounting for the majority of villages and families.

4 The survey was conducted in 1998-99 in seven villages (mouzas) spread over

all the five agro-climactic zones of West Bengal. It was our privilege that

we had with us unprocessed data from a similar survey – based on the same questionnaire

and methodology (the census system) – conducted in these and other villages

in 1978 by a group of left intellectuals> it was thus possible to compare the

two sets of data.

5 Pump-shallows refer to a modified combination of diesel and electrical machines,

which increases efficiency in lifting water.

>>>>>>>>>

Figures

1 and 2 show that rural mean per capita consumption as well as the head count

ratio of rural poverty rose and fell in West Bengal more or less in tandem with

the rest of the country, showing hardly any sustained special achievement. We

have reproduced these figures from Haris Gazdar and Sunil Sengupta (Ben Rogaly

et al, 1999). Basing himself on the 50th Round (July 1993 to June 1994) of NSS

data, Ranjan Ray made very detailed estimates of rural and urban poverty. In

Table 3 we present some of his findings, which show that in terms of all the

available indices of rural poverty, West Bengal stood below the national average

and fared better than very few states. (Ray, 2000) On the other hand, the LFG’s

performance in providing subsidised foodgrains to the rural poor is admitted

to have been worse than that of state governments run by reactionary parties,

such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Figures

1 and 2 show that rural mean per capita consumption as well as the head count

ratio of rural poverty rose and fell in West Bengal more or less in tandem with

the rest of the country, showing hardly any sustained special achievement. We

have reproduced these figures from Haris Gazdar and Sunil Sengupta (Ben Rogaly

et al, 1999). Basing himself on the 50th Round (July 1993 to June 1994) of NSS

data, Ranjan Ray made very detailed estimates of rural and urban poverty. In

Table 3 we present some of his findings, which show that in terms of all the

available indices of rural poverty, West Bengal stood below the national average

and fared better than very few states. (Ray, 2000) On the other hand, the LFG’s

performance in providing subsidised foodgrains to the rural poor is admitted

to have been worse than that of state governments run by reactionary parties,

such as Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu.

Coming

to the question of devolution of power, recent studies – including one by the

West Bengal government itself – has found that the onetime frontrunner now lags

behind some other states. Early this year, Matreesh Ghatak and Maitreya Ghatak,

after taking note of the “admire[able]…achievements of West Bengal as a pioneering

model of participatory government,” pointed out: “A recent inter-state study

by Jain (1999) covering all the major states put West Bengal not only behind

Kerala but Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka on indicators such as the power to prepare

local plans, transfer of staff, control over staff, transfer of funds…Further

more, a committee set up by the West Bengal government itself has criticised

the district level planning process involving the panchayat system and state

bureaucracy for lack of coordination and insufficient participation of the people,

or their elected representatives, at the village level…The state government

bureaucracy hands out district plans to district officials and lower tiers of

panchayats have no say in the allocation of these funds or the implementation

of these projects, unless they are requested to lend a helping hand. The amount

of money spent through this channel is much more than that is directly handled

by panchayats. Also, there is little attempt at coordinating between these two

sets of plans at the district level [Government of West Bengal, p.6],” (Ghatak

and Ghatak, 2002)

Coming

to the question of devolution of power, recent studies – including one by the

West Bengal government itself – has found that the onetime frontrunner now lags

behind some other states. Early this year, Matreesh Ghatak and Maitreya Ghatak,

after taking note of the “admire[able]…achievements of West Bengal as a pioneering

model of participatory government,” pointed out: “A recent inter-state study

by Jain (1999) covering all the major states put West Bengal not only behind

Kerala but Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka on indicators such as the power to prepare

local plans, transfer of staff, control over staff, transfer of funds…Further

more, a committee set up by the West Bengal government itself has criticised

the district level planning process involving the panchayat system and state

bureaucracy for lack of coordination and insufficient participation of the people,

or their elected representatives, at the village level…The state government

bureaucracy hands out district plans to district officials and lower tiers of

panchayats have no say in the allocation of these funds or the implementation

of these projects, unless they are requested to lend a helping hand. The amount

of money spent through this channel is much more than that is directly handled

by panchayats. Also, there is little attempt at coordinating between these two

sets of plans at the district level [Government of West Bengal, p.6],” (Ghatak

and Ghatak, 2002)