The other

side of the euro coin

The other

side of the euro coin

The other

side of the euro coin

The other

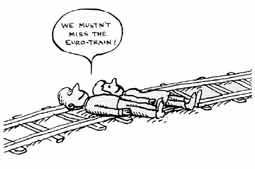

side of the euro coin [While the introduction of the euro is bound to fuel rivalry between the euro and the dollar and intensify the trade war between the US and the EU, it has an anti-people and anti-worker flipside. A brief commentary by Mikael Nyberg.]

The euro, the currency of the European Union, has now reached shops, news-stands and petrol stations in the member states taking part in the experiment.

“A historic moment”, Romano Prodi, chairman of the European Commission says.

Politicians in the European Union have propagated the euro as protection against the whims of global capital markets, a strong currency that will save the welfare of common people in Europe. Even some leftists are arguing along this line.

Will these visions now come true? Hardly.

The European Monetary Union has been at work for some years already. Long before consumers in Europe got their hands on the new coins and notes, the euro was traded by companies, banks and other financial institutions. It has conquered 35 per cent of the international capital market, second only to the dollar, which has 45 per cent.

But so far it has not proven to be any protection against the financial fluctuations of global capitalism. Like many other currencies the euro has weakened against the dollar. It has weakened even more than the currencies of the countries in the EU which have not introduced the euro (Sweden, Denmark and the UK).

More important, the euro was never intended to be a weapon against capitalist globalisation. On the contrary, the statutes of the monetary union are instruments for furthering this process. Regulations of the flows of finance capital are not allowed, and the right to dictate monetary policy in the union has been transferred to the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt. This means that unelected bankers, explicitly forbidden to listen to popular opinion or take instructions from parliaments, have the power to veto or obstruct any political decision in the EU deemed not to be in the interest of what is called “healthy economic growth”.

ECB is supposed to fight inflation, but it is doing this in a typically peculiar way. The struggle against inflation does not apply to price rise in general. It is first of all directed against rising prices on labour power. If wage earners get more money to buy food and other necessities, and prices of bread and butter start to rise, economists and politicians make noise about inflation and economic crisis. When, on the other hand, prices on stock markets rise by 50 to 60 per cent a year, they just enjoy good times. Stock prices are not part of the indexes measuring inflation. Provided incomes of working people are kept in check, central bankers can expand money supply without risking any major acceleration of measured inflation. Money will instead flow into the hands of capitalists investing them on the stock exchange or in real estate.

Central bankers in Europe, like in the United States, have for some years flooded the markets with liquidity. This policy has contributed to the largest financial boom and bust since the Great Depression. Trying to stem the tide and rescue the heroes of dotcom and telecom mania, the ECB is now expanding monetary supply at a rate of over 7 per cent a year.

On labour markets and in the public sector there is no trace of this generosity. Members of the euro area have to follow a set of strict convergence criteria, limiting budget deficits, government debt and inflation. These rules, and the dictates of central bankers, are keeping a tight lid on wages and social expenses.

Sweden, whose government has not yet dared a referendum on the euro, nonetheless applies the convergence criteria. This has hastened privatisations and cutdowns in social welfare. De-regulations of labour markets are also on the way. In the new currency area Swedish businesses would be unable to use devaluations to handle external shocks or wage demands out of step with the rest of EU. They have therefore, quite successfully, demanded a weakening of the position of workers.

“We can’t have stricter rules than others on the labour market”, Sune Ehring, vice president at the Swedish Employers’ Federation, says.

These effects of the euro-project are even more pronounced in countries of eastern Europe, struggling to qualify for membership in the European Union. The crisis in Argentina has demonstrated the dangers of surrending to stronger currencies and giving up national instruments of monetary policy. In Poland the euro-inspired policy of the central bank has already caused an uproar.

The ECB will adjust monetary policy to the interests of the strongest member states, but unity and harmony is not garantueed even among these nations. If the economies of countries like France and Germany develop in different directions, sharp contradictions will shake the project.